Aircraft

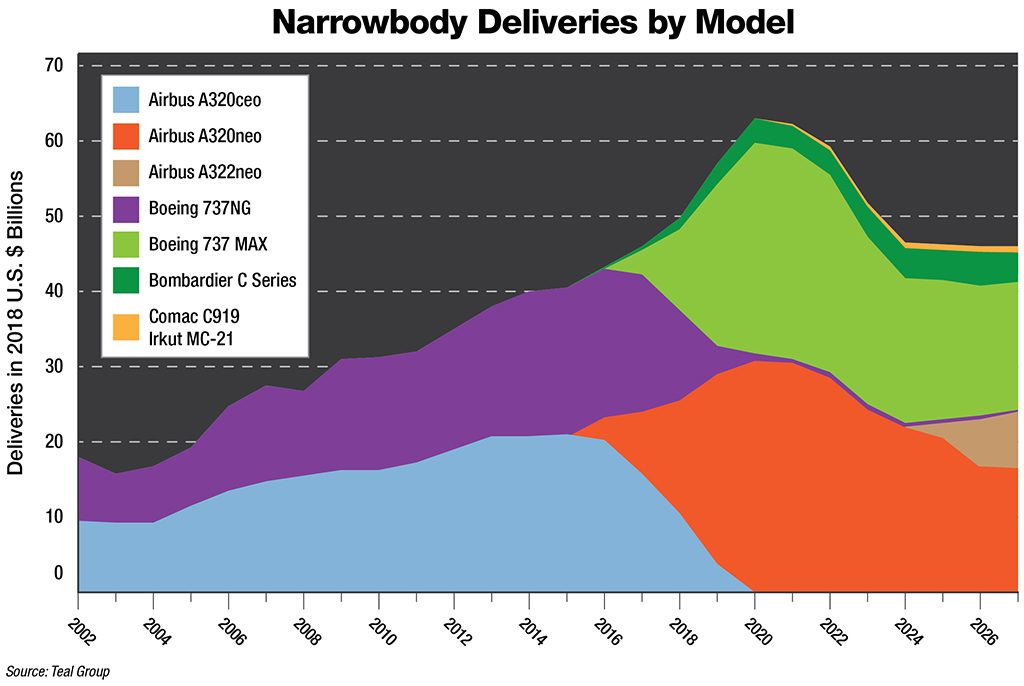

If there is one word that describes the state of the narrowbody market, it is “unprecedented.” Never have so many different models either entered or been prepared to enter service by so many manufacturers, and never have demand and production reached such high levels as in the past several years—though this production surge has been accompanied by serious supplier issues. Yet, in spite of the huge demand for existing Boeing and Airbusproducts, there is mounting uncertainty about the future product strategy of the two market leaders.

This is a year of transition for almost all involved players. It is the last year in which the classic Airbus A320 family and the Boeing 737NG will be produced in large quantities. Starting next year, the A320neo and the 737 MAX will dominate. This year, not only is the first serious production ramp-up of the Bombardier C Series occuring, but so is its imminent integration into the Airbus product portfolio—with regulatory approval expected by midyear. At the same time, Embraer has delivered the first E190-E2, an aircraft it hopes will become a significant player at the lower end of the narrowbody market along with its larger variant E195-E2, which is scheduled to enter service next year.

Airlines have more choice than ever when selecting narrowbody fleets

Comac and UAC are poised to deliver aircraft but focus on home markets

Strategic positioning of Embraer and Bombardier changes

New competitors also are being prepared for commercial service, with the United Aircraft Corp. (UAC) MC-21 and Comac C919 in flight tests. Their market penetration will likely be limited mostly to their home countries, but in the case of the Chinese C919, that is a nice problem to have.

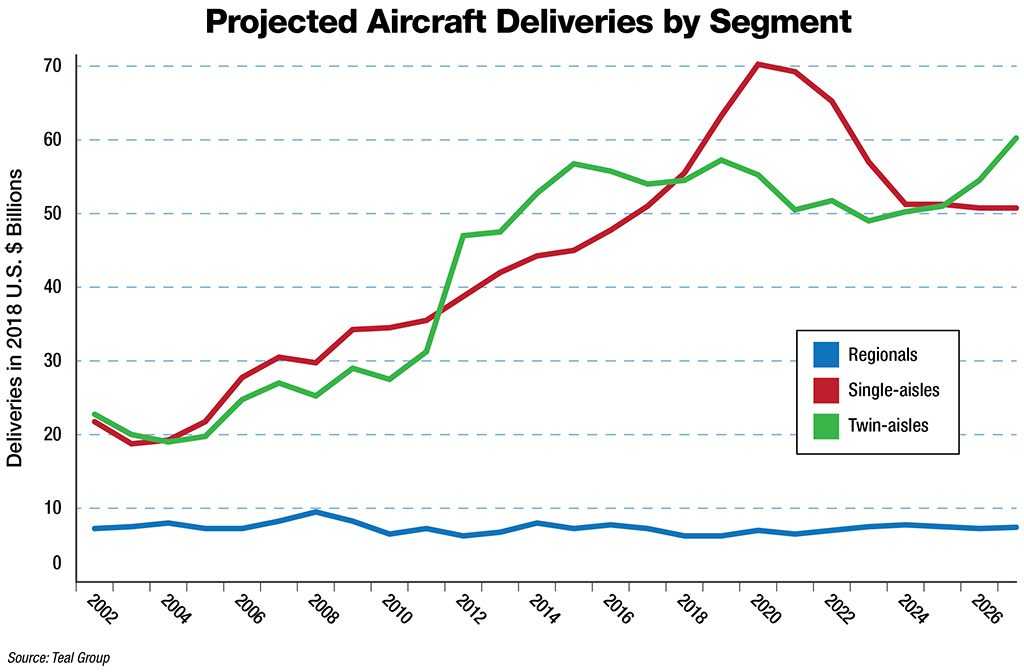

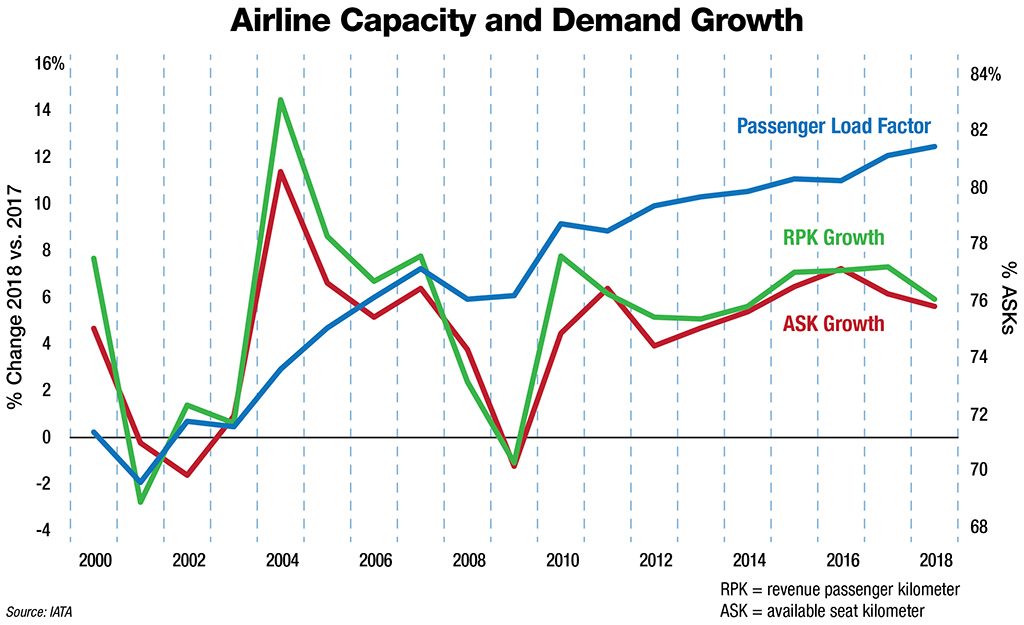

However, these events are not taking place in a vacuum. “The last eight years have witnessed an unprecedented (except for the 1960s, the first years of the jet airplane) run of world traffic growth of 7% almost every year,” Edward Greenslet writes in The Airline Monitor, a regular in-depth analysis and forecast of industry trends. “Not only are producers seeing strong demand for their products, the airlines behave as if the recent traffic numbers are the new normal.” Greenslet adds that “both sides of the demand equation are, in effect, proceeding on the assumption that recent conditions will continue indefinitely.” That is a mistake, he believes, because “the prospect of seeing a time of lower demand is as near to a certainty as anything can be. The only question is when.”

But for now, no one seems bothered. In fact, because of the current demand growth for air travel, “deliveries for this and next year are actually below what the industry needs, lending support to the rate increases that are planned,” Greenslet states.

And so at this stage, production can only accelerate, driven primarily by Airbus.

Airbus CEO Tom Enders says he can “absolutely see a basis” for an output of 70 or more A320neo-family aircraft per month “from a commercial point of view.” The aircraft maker is in the process of moving to build 60 narrowbodies per month in mid-2019 from a production level in the mid-40s at the end of 2017. Chief Commercial Officer Eric Schulz says 63 per month is the next step. “We look at rates all the time; why would we not contemplate going higher?” Schulz asks. “Demand is very strong, and there are a lot of opportunities.” At the same time, “we have to deliver a complete aircraft, and suppliers have to be able to support the increase,” he adds.

Which describes exactly Airbus’ problem. In the first three months of 2018, the OEM delivered only 95 single-aisle aircraft, just over 30 per month and well short of its own targets. “We have dozens of gliders parked in Toulouse and Hamburg,” Enders says, referring to A320neos and A321neos awaiting Pratt & Whitney PW1100G engines.

Airbus was forced to suspend deliveries of Pratt-powered aircraft in early February after a recently introduced modification to the engine led to several inflight shutdowns and aborted takeoffs. Deliveries have yet to be resumed; Enders also has publicly highlighted delays in engine deliveries by CFM International, which provides the alternative powerplant, a clear sign of Airbus’ sense of urgency around the issue. Enders clearly expects 2018 deliveries to be even more “backloaded“ than last year. The company delivered 718 aircraft in 2017, more than 100 of which were handed over in December. The OEM wants to deliver about 800 aircraft in 2018, most of them single-aisle jets and a growing portion of them Neos.

A320neo-family deliveries are still dominated by the A320neo, although the A321neo’s share is rising. Greenslet believes the A321neo “certainly appears to have come closer than any other model to defining the sweet spot for single-aisle aircraft over the next two decades.” The A319neo is currently still in flight tests and is planned to be delivered to its first operator in 2019. Much more important, next year also marks the entry into service of the A321LR, which is capable of long-haul missions across the Atlantic, from Europe to Asia or North America to Brazil.

At the same time, Airbus is pushing out a decision on whether to go ahead with upgrades of its A320neo-family aircraft. Schulz says that “we cannot fix everything at the same time,” referring to in-service issues, the output increases and potential product development. While “we don’t cancel anything,” Airbus’ management has come to the conclusion that “we need to deliver what we committed to first.”

Airbus has been studying both minor and more substantial upgrades to the A320neo and A321neo, dubbed A320neo plus and A32neo plus-plus. Both studies entail stretching the aircraft, while the plus-plus variant would include more difficult changes such as a new composite wing. Industry reaction to the plans has been mixed.

The project was at least partially designed as a response to Boeing’s proposed new midmarket airplane (NMA), which has yet to be launched. Airbus management’s thinking centers on being able to provide an upgraded version of the A321neo well ahead of the expected NMA entry into service. While there have been expectations of an NMA launch decision this year with the aircraft entering service around 2025, Boeing is still working out the business plan—and aircraft pricing in particular—and there has been speculation the aircraft may come later than anticipated. If that happens, Airbus would gain time to fix problems with the current model, ahead of jumping on to a new version, as well as allow it to further consider its product strategy. If Boeing moves ahead sooner, Airbus may risk coming under more pressure for a strong reply.

Boeing, meanwhile, continues a fine balancing act at its facility in Renton, Washington. It is simultaneously pumping out 737s at unprecedented rates, introducing a new model into the production system and readying for development of the stretched -10 next year.

As it moves into the next critical phase of its MAX introduction strategy, Boeing knows it cannot afford any slips, with the 737 increasingly vital to its cash flow. Of the 184 Boeing commercial aircraft delivered in the first quarter of 2018, some 132 were 737s, including the 10,000th member of Boeing’s smallest jetliner family—a 737-8 MAX for the new variant’s launch customer, Southwest Airlines.

Since the first 737-8 was handed over in May 2017, deliveries of the MAX have begun to accelerate on plan with 74 in the hands of operators by the end of December and another 40 by late April 2018. The tally includes the first 737-9, which was delivered to Lion Air in March 2018. The Indonesian-based low-cost carrier also made headlines in early April when it was confirmed as a previously unidentified customer for 50 737-10s.

Boeing, which is completing detailed design of the higher-capacity derivative this year, plans to begin flight tests of the final stretch model in 2019 and initiate deliveries in 2020. About 416 737-10s have been ordered by 18 operators since its launch at the 2017 Paris Air Show. Although this appears to be a relatively small portion of the 4,474 firm orders for the entire 737 MAX family announced through the end of March, Boeing says more than 1,500 positions are currently undecided or unknown.

As the higher-capacity model is Boeing’s principle counter to the highly popular A321neo, the company is also eager to bolster marketing and sales efforts for it, looking to sustain the MAX production line through the late 2020s. This year could be a vital one for sealing several campaigns with airlines that have been maintaining a watchful eye on the new stretch variant. According to Boeing, these potential customers have signed off on the finalized design of the novel landing-gear configuration that enables a 66-in.stretch over the 737-9, for an overall length of 143 ft.

The -10 extension consists of a 40-in. plug in the forward fuselage and 26 in. aft. The completely revised taller main landing-gear design, which combines a telescoping feature to shorten the leg and a semilevered lower element to move the aircraft takeoff rotation point aft, still fits within the existing wheel well but can extend to raise the body a further 9 in.

Although Boeing is reluctant to provide details of its backlog breakdown, there is no disguising the 737-8’s popularity. With an orderbook estimated at almost 2,330, the 737-8 accounts for the overwhelming majority of declared MAX orders. However, as narrowbody operators continue to upgauge and trend toward larger-capacity models as traffic and range capability grow, questions remain about the future 737-9 orderbook and to what extent it will be cannibalized by the newly available 737-10.

Announced orders for the 737-9 amount to a relatively modest backlog of about 116, but the true tally is thought to be more than 400. However, some erosion has inevitably taken place since the -10 became available, notably from United Airlines. In 2012, it became one of the main customers for what was then the largest variant, along with Lion Air, when it ordered 100 MAX 9s. United was among several operators that converted -9 orders to -10 in mid-2017, when the new model was firmly launched.

The U.S. carrier, which is expected to take its first three 737-9s by the end of April, converted 39 MAX 9 orders to the -10, but with 61 firm positions, it still remains the single largest acknowledged customer for the 737-9. United is expected to receive up to 10 aircraft in 2018 and will put the first of the 179-seaters into service around midyear on routes from Houston and Los Angeles to Anchorage, Alaska; Austin, Texas; Fort Lauderdale, Florida; Honolulu; Sacramento, California; and San Diego.

While boosting the orderbook for the upper end of the MAX family against the A321neo is urgent business for Boeing, the situation is arguably more critical at the lower end, where flight tests of the 737-7, the smallest member of the series, began on March 16. Despite a redesign of the -7 in 2016 at the request of launch customer Southwest Airlines and WestJet of Canada that added range and an extra 12 passenger seats to provide capacity for 138 in a typical two-class layout, the market reaction remains lukewarm.

Boeing is scheduled to spend the bulk of this year on the flight-test and certification program before delivering the initial 737-7 in 2019. The OEM also is banking on positive performance results from the test campaign to stimulate orders, which officially stand at fewer than 60. Boeing believes the aircraft’s range capability of 3,850 nm, the longest of any MAX version, could make it an attractive niche player for airlines looking to open new point-to-point routes in much the same way as the 787 has been.

Key to this capability are the aerodynamics of the MAX wing and redesigned tail cone, plus the propulsion improvements provided by the CMF Leap 1B. Together, these allow the MAX 7 to fly 1,000 nm farther and carry more passengers than its predecessor, the 737-700, and with 18% lower fuel cost per seat. Boeing thinks this gives the MAX 7 the advantage over its nearest rival, the Airbus A319neo. The aircraft, it says, carries 12 more passengers 400 nm farther than the smaller Airbus, with “7% lower operating costs per seat.” Other close rivals in the tightly contested 130-seat sector include Bombardier’s stretched CS300 and Embraer’s 195-E2.

Flight tests of the initial 737-7 appear to be on track, with the aircraft focused on certification high-speed air testing. A second aircraft is expected to join the flight-test program shortly.

After its market introduction in 2016, the Bombardier C Series is now about to enter a transformative phase, with Airbus nearing regulatory approval to take majority control of the program. There are differing views on how that will change the aircraft’s prospects and whether Airbus marketing efforts will be enough to turn around its fortunes. One school of thought is that nothing much will change, because Airbus sales representatives will prefer to sell the larger narrowbodies.

A different take is that Airbus will push the C Series hard because,absent a merger agreement with Embraer, Boeing has little to counter with. What is clear, however, is Airbus’ drive to reduce C Series production and supplier cost, the effects of which the OEM’s suppliers will likely see soon after the transaction has been approved.

Also new to the scene is the Embraer E2, with its predecessor still largely limited to regional operators. Embraer’s business case for the E2 rests on the assumption of much higher production volumes, so the aircraft needs to succeed in new market segments. JetBlue Airways is close to a decision on how to replace its current E1 fleet. If it opts to stay with the Brazilian manufacturer, the program would receive a major boost and send “a strong signal to the market,” says Embraer Commercial Aviation President and CEO John Slattery. Other campaigns, primarily in North America and Europe, are ongoing.

In China, two Comac C919 prototypes are in the air, with a third due to join the flight-test program this year. C919 development is working to achieve airworthiness certification in 2020, says the Civil Aviation Administration of China.

The agency reiterates Comac’s previously stated target of first delivery in 2021. As of early March, the first and second prototypes had flown 23 times, Comac chief designer Wu Guanghui said at the time. They first flew in May and December 2017, respectively.

The third aircraft is expected to make its first flight “before the end of the year,” Wu says. “In 2019, it is planned to have three more aircraft in flight testing, for a total of six.” That will complete the flight-testing fleet, according to current plans.

The second C919 has been under modification at Shanghai, where Comac is based, and is due to move to Comac’s flight-testing base at Dongying in April. These two aircraft will be used for hot- and cold-soak testing, too, Wu says.

At least nominally, the program would be protected by tariffs that China, responding to Washington’s taxes on Chinese goods, said on April 4 it would apply on U.S. goods. These included aircraft with empty weights of 15-45 metric tons (33,000-99,000 lb.). The upper end of that range was evidently defined by the C919’s specifications.

In practice, the tariff’s influence on the C919 program is unlikely to be great, if it is even imposed, because the consistently Chinese nationality of the program’s customers indicates politics, not competitiveness, is the chief influence on orders.

The last reported test flight of the Irkut MC-21, Russia’s new narrowbody aircraft, was in early November. Since then, neither Irkut Corp. nor UAC has revealed anything about the testing, although Irkut says certification trials of the MC-21-300 narrowbody airliner continue, without providing further details.

The testing is now limited to one prototype. It was rolled out in June 2016 and took off for the first time in May 2017. After completing 20 flights under the factory test program in Irkutsk, the aircraft flew for certification trials to the Gromov LII Flight Research Institute in Zhukovsky, near Moscow, in October.

The second MC-21 prototype was rolled out at the Irkut facility in Irkutsk on March 25. The manufacturer reported that the second prototype had been assembled taking into account the results of the trials of the first aircraft.

Irkut did not say when the second prototype will fly, but Russian media cited an Irkut representative saying this could happen in May. The second prototype is expected to speed up the trials. “The introduction of new aircraft to flight tests will enable us to solve the key tasks of the program: to complete the certification of MC-21 in a timely manner, to launch mass production and to deliver the first airliners to the customer,” says Denis Manturov the Russian minister of industry and trade.

The third prototype was spotted in the final stages of assembly. Irkut says it has begun building the fourth test aircraft.

The company plans to receive Russian type certification for the MC-21 in mid-2019, to be followed by European Aviation Safety Agency validation a year later. The MC-21-300-baseline version will carry between 163 and 211 passengers over a distance of 6,000 km (3,700 mi.). It will be powered initially by a pair of PW1400G-JM engines.

The fourth prototype is expected to be equipped with Russian PD-14 engines in the second quarter of 2019. This engine is expected to get Russian certification later this year. The certification of the PD-14-powered MC-21 variant is planned for 2021.

The MC-21 backlog stands at 175 firm orders, mostly from Russian leasing companies. The country’s largest carrier, Aeroflot, is expected to be the major operator of this type. It firmed up its order for 50 aircraft through Avia Capital Services, a leasing arm of Rostec Corp., in February and is set to take the first delivery in early 2020.

Article source