Jan 26, 2017 – The part-out process is an option for aircraft owners. Part-out candidates can range from young aircraft variants with a large user base. to older types that are gradually being phased out. The part-out process is examined here along with potential values and disassembly providers.

Teardowns and End-of-Life Solutions

Every year 500-600 commercial passenger and freighter aircraft are withdrawn from service. Some of these might be placed in long-term storage, but many are disassembled. The number of organizations offering teardown or part- out services has increased in recent years. The part-out process is described here. Potential part-out candidates and resulting asset values are considered. Some of the main teardown service providers are also summarized.

The part-out market

The part-out process involves an aircraft being withdrawn from service and dismantled. Engines and other components are removed and either returned to stock to support the rest of the fleet, or made available for sale or lease so that the owner can maximize asset values.

Aircraft might be parted out when they still have years of operational life remaining because owners believe the sum of the parts is worth more than the revenue that could be obtained from continued operations. Alternatively, an aircraft may be parted out as it approaches its utilization threshold or when it becomes obsolete.

Aircraft might belong to different types of owner when they are parted out. These include airlines, leasing companies, banks, specialist investment funds and parts trading companies.

Mike Corne, commercial director at eCube Solutions, believes that airlines account for only a small percentage of global part-out demand. “Generally only the major operators will directly part out aircraft, typically when they are in the process of phasing out a particular type and are trying to minimize further spares investment in these aircraft,” says Corne.

Banks and leasing companies may occasionally be customers in the part-out process, but typically dispose of aircraft before they are disassembled. “A leasing company’s business is fundamentally about earning revenue from the lease of operating aircraft,” says Corne. “They do not want to own 1,000 small component assets taken from parted-out aircraft.

“In the past five years, a number of specialist investment funds have raised capital to acquire aircraft that they have evaluated to be worth more as parts than as a whole asset,” continues Corne. “These comprise 60-70% of the actual owners of part-out assets.”

Parts trading specialists

In many cases, aircraft are sold or consigned to parts trading specialists shortly after they are removed from service.

“Parts trading companies probably own about 25% of the aircraft that are parted out,” estimates Corne. “They also manage a large percentage of part-out projects on a consignment basis from third-party owners, which in most cases are specialist investment funds.”

Touchdown Aviation (TDA) is a parts trading specialist with experience of the part-out market. TDA is headquartered in the Netherlands, but has recently opened a new facility in the UK. It offers aircraft component sales, leasing and exchange programs. “We focus on narrow-bodies, including younger A320 family airframes and 737NGs,” explains Julian Marcus, managing director at TDA. “Acquiring aircraft for part-out has allowed us to enlarge our inventory faster and at more competitive prices.”

TDA manages part-outs for aircraft it has acquired directly or that it manages on a consignment basis for third-party owners. “Under the consignment process, the parts trader and owner agree on the percentage each party receives when the consigned material or components are sold,” explains Marcus. “The consignee handles everything in terms of logistics, marketing and the sale of the components, which are owned by the third party.”

AJW Aviation is another parts trading specialist with experience of the part-out market. It provides component sales, loans, exchanges, power-by-the-hour (PBH) support and parts pool access, among other services. The part-out process is appealing to parts specialists like AJW Aviation, because it provides an avenue for them to obtain high-demand component items at lower costs to support their PBH and sales activities.

Selling or consigning an aircraft for part-out to a parts trading specialist allows third-party-owners to make returns on component asset values without having to invest in developing skills and experience outside of their core business activities.

AJW Aviation has previously bought its own aircraft to part-out, but has also managed the process under consignment agreements. “In the future we want to perform most part-outs on a consignment basis,” explains Conrad Vandersluis, vice president of strategic material and asset management at AJW Aviation.

“AJW Aviation plans to manage the part-out process for up to 10 airframes and 30 engines in 2016,” continues Vandersluis. “The CFM56-5B, CFM56- 7B and V2500-A5 are engine types of focus both for consignment or purchase, because of the longevity of material requirements for these engines for the foreseeable future.”

Parts trading specialists will contract a third-party dismantling provider to tear down an aircraft in most cases. There are occasional exceptions to this rule, with some organizations providing combined trading and dismantling services.

Some components will be removed from the part-out aircraft in serviceable condition. Others may need to be sent for inspection, repair or overhaul.The parts trading company may have some in- house repair and overhaul capabilities, but in many cases this work is performed by a third party.

“Parts are removed in serviceable condition in accordance with the aircraft maintenance manual (AMM) during the dismantling process,” explains Vandersluis. “We aim to maximize the reliability of components in our inventory, so we tend to send removed items to a repair shop for more rigorous testing in accordance with the component maintenance manual (CMM). AJW Aviation is part of the AJW Group, which also includes AJW Technique, a component repair facility in Montreal, Canada. AJW Technique’s approvals include avionics, hydraulics, pneumatics and electrical and lighting components. AJW Aviation sends 14% of its components to AJW Technique for inspection, repair or overhaul as required. AJW Technique provides us with high- reliability repairs and competitive rates, which helps us to control re-certification costs.

Engines and components will be returned to the parts trading company once they have been removed and, if necessary, sent for inspection or repair. They will then be added to its spares inventory where they will be made available for sale, lease and PBH component support services.

Some parts trading companies like AJW Aviation will part out airframes and engines. Others, such as Aviall, only focus on engines. “Aviall continues to work with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to meet and anticipate the needs of their complete lifecycle engine business,” explains Sheena Mitchell, vice president commercial engines and rotor- wing programs at Aviall. “We provide engine parts and service support to our OEM partners through distribution agreements and unique programs. These agreements often involve forecasting, ordering and delivering OEM replacement parts through our worldwide distribution and supply chain capabilities. Materials from our asset part-outs are used to complement our OEM aftermarket offerings and support several OEM PBH programs.”

Many of the larger parts trading companies will be more interested in younger aircraft types with large fleets and high component demand, such as the 737NG and A320 families, because they have higher asset values. Some other parts traders might specialize in the part- out of older types with fewer in-demand and lower value components.

The dismantling process

It is not unusual for an aircraft to enter a short period of storage following its withdrawal from service while ownership changes hands and final decisions are made regarding its ultimate fate. Many dismantling providers also offer storage services.

“A typical scenario would see an airline deliver an aircraft to a dismantling facility at the end of lease on behalf of the lessor,” explains Mark Gregory, managing director at Air Salvage International (ASI) “Some aircraft may enter a brief storage period lasting several weeks while the lessor decides what to do with the asset.”

Some dismantling companies will be approved Part 145 maintenance providers, or will work closely with a partner or affiliate Part 145 organization. This allows them to provide necessary care and maintenance during any storage periods. “The aircraft is brought in under care and maintenance,” explains Gregory. “We then work with the lessor to satisfy lease transition maintenance requirements. In most cases, the aircraft will be sold or consigned to a parts trader before the physical teardown process begins.”

“When an aircraft arrives for parting- out, the crew is debriefed for any incoming defects and the technical log is consulted to identify any deferred defects,” explains Gary Spoors, managing director and accountable manager at GJD Services. “The aircraft is then made safe, by de-arming the slide packs and fitting safety pins and locks as needed.

“For re-certification requirements, full-power engine ground run performance checks are carried out,” continues Spoors. “These are followed by system operational tests, including flight control and autopilot checks, and checks of the PA system and toilets. The engines are inhibited when all of the necessary checks have been completed.

“The next stage is to configure the aircraft for dismantling,” says Spoors. “This involves lowering the flaps, raising the speed brakes, dropping the landing gear doors and positioning flight surfaces as required for removal. Upon completion, all the extra spoiler locks, gear door locks and gags are fitted to prevent inadvertent operation and relevant circuit breakers are pulled to prevent the operation of systems. At this point the hydraulics are drained, the fuel is removed, tanks are opened for venting and all gaseous systems are deflated.”

“The engines and high value components are removed after the liquids have been removed,” explains Derk-Jan van Heerden, chief executive officer and founder at Aircraft End-of-Life Solutions (AELS).

Depending on the level of demand and maintenance status, engines may not be parted out with the rest of the aircraft. “Engines have their own lifecycle that is not parallel to that of the airframe,” says van Heerden. “You could have an end-of- life airframe with young engines, or a valuable airframe with end-of-life engines. Each aircraft that is disassembled

will bring two engines on to the market. These may be disassembled for parts, leased out, used internally or scrapped for their metal value.”

Since airframe and engine life cycles are not necessarily in sync, some engines may be parted out independently of any airframes.

Spoors says that once the engines have been removed, items including the auxiliary power unit (APU), avionics, flight control actuators and air- conditioning and hydraulic systems components take priority. The interior is then removed, including the seats and carpets. “Any remaining items that contain carbon fibers, such as the fin and tail plane on some aircraft, are removed for specific disposal,” explains Spoors. “It is essential these materials are treated in the correct manner, because they contain fibers that are smaller than asbestos fibers, and can severely affect a person’s health if they are breathed in. The disposal of such materials comes with additional associated costs.”

“The last item to be removed is the landing gear,” says van Heerden. “If components are removed by a Part-145 approved maintenance organization they can be recertified on removal as ‘Serviceable As Removed’, subject to test, inspection and record review,” explains Spoors. “The aircraft needs to remain registered during the part-out process, and have a current Certificate of Airworthiness (CofA) or Airworthiness Review Certificate (ARC), for parts to be removed as serviceable. Parts are normally shipped straight to the customer that owns the asset. If they need a shop visit they may well sit on a shelf until a demand arises.

“After all of the main components have been removed a final walk-through and associated check take place,” continues Spoors. “The empty hull is crushed and sheared, and the scrap metal is sent for recycling.”

Part-out candidates

A number of scenarios could lead to certain aircraft types or individual airframes becoming part-out candidates.

“Part-outs provide airlines with a cheaper alternative for spares to maintain their fleets,” explains Stefan Haynes, vice president sales EMEA at GECAS Asset Management Services (AMS). “Parting- out is a good option whenever it is no longer economically advantageous to continue operating an aircraft. The part- out process may also appeal to operators looking to exit an aircraft type entirely or for those who want to retire an aging fleet.

“To conserve cash an operator might consider parting out an aging aircraft (15 plus years) that is due a heavy maintenance check,” continues Haynes.

“Aircraft owners consider their options each time a high-cost event arises at the end of a period of operation, such as a lease return,” says Corne. “This might include an engine performance restoration or heavy structural airframe maintenance. If it makes economic sense, they may decide to sell the aircraft as a part-out candidate and cash in on any maintenance reserves, rather than invest in restoring the aircraft to a condition for a further period of operation.”

A downside or risk with part-out is that as the fleet for a type diminishes in numbers, the quantity of material and spares from dismantled aircraft increases, while demand from a small fleet reduces.

“Another typical part-out scenario is when an operator goes bust leaving a fleet of aircraft behind,” explains Spoors. “An example of this is when Spanair ceased flying. Those aircraft were in Spanair livery, with Spanair seats and Spanair internal trim. That’s a lot of capital expenditure (Capex) just to re-lease the aircraft. The owner then starts to look at when the heavy maintenance is due and that seals the aircraft’s fate.”

“Aircraft that have been operated under harsh conditions, have missing maintenance records or are maybe even incident-related, can also become part- out candidates,” says van Heerden.

“Some countries have age limits on commercial aircraft, which can make certain airframes strong candidates for part-out,” says Haynes.

“Part-out demand typically starts after first-tier carriers move their stock to second-tier operators,” says Spoors.

“A typical age-range at which aircraft become suitable for part-out is 15-20 years, but it depends on the aircraft type,” says Haynes.

Aircraft might be parted out at an even younger vintage if the owner thinks this approach will offer the best return on investment. Gregory says that the average age for A320 family part-out candidates is about 18 years, but that ASI has processed a number of 12-15-year old examples, and even one aircraft as young as seven years.

Other aircraft will be parted out at much older vintages, as their accumulated utilization approaches operational limits of validity.

For owners of younger in-production aircraft variants the part-out process is one of several options to maximize remaining asset value. “Depending on the vintage of the aircraft, alternatives to parting-out can include selling it or continuing to use it as a flyer, converting it to a freighter, selling it as a training aid or prop, or completely scrapping it,” says Haynes.

Passenger-to-freighter (P-to-F) conversions have traditionally been considered economically viable when aircraft are 15-20 years of age. Some aircraft types are being converted at up to 25 years old in the current market. P-to-F conversions are only available for certain types, however. There are few alternatives to the part-out process for aircraft older than 25 years, should the owner consider it uneconomic to continue passenger operations. “Sometimes it is cheaper to park the aircraft, rather than cover the cost of disposal, but those disposal costs will get more expensive,” says Spoors.

“An aircraft that is disassembled as soon as possible after its last flight is considered a better part-out candidate from a technical point of view because the components will still be in operational condition,” says van Heerden. “The longer an aircraft is parked the more likely it is that their condition will deteriorate.

”The most likely teardown candidates in the current market can be sub- categorized into high-demand and low- demand part-out candidates.

High-demand candidates

High-demand candidates are generally relatively young airframes of no more than 10-15 years of age, for which the part-out process is preferred over alternative use options, includingcontinued passenger operations or P-to-F conversion.

“The newer the aircraft model, the higher the parts demand and the higher the component value,” says van Heerden. “This makes younger types more interesting disassembly candidates. In that field, however, you are also competing with potential buyers who want to fly the aircraft.”

“Aircraft types that have a large operational user base and a low retirement rate can become more valuable as parts than as flying machines,” says Spoors. “Aging aircraft with high in- service numbers are ideal part-out candidates,” concurs Haynes.“Aircraft variants that have been superseded by newer models, but where a strong level of parts commonality remains between the different generations are also good candidates,” adds Haynes.

In the current market the most in-demand turboprop part-out candidates include first generation ATR 42s and ATR72s and Bombardier Q400s.

The most in-demand regional jet (RJ) part-out candidates include older E-Jets.

The most in-demand narrow-body candidates are 737NGs including the -700 and -800 series, and younger A320 family variants including A319s, A320s and A321s. “There are quite big differences between early line number A320 family aircraft and later-build aircraft,” explains Vandersluis. “First, there are three distinct variations of avionics fit for the A320 family, with no real commonality between them. Early aircraft also had different APUs and slight differences related to the landing gear. EIS2 standard A320 family aircraft manufactured from about 2003/2004 onwards are the most desirable part-out candidates in terms of component value.

”The most appealing wide-body part- out candidates from a parts demand perspective are A330s and 777-200s.

Lower-demand candidates

Aircraft types for which there is less demand for aftermarket spares will see less demand as part-out candidates.

This might include aging types in excess of 15-20 years of age that are being retired from service, resulting in a contraction in the active fleet and in many cases an oversupply of aftermarket spares. These aircraft will have few alternative options to the part-out process. This may lead to high numbers of part-outs for certain types, regardless of the lack of demand for associated spares and the resulting impact on asset values.

“At a certain moment in time individual aircraft or variants will become less desirable from an investment point of view,” says van Heerden. “Their continued operation is then the only alternative to parting-out. All aircraft that reach end-of-life need to be disassembled. We cannot park them somewhere and walk away.”

“There is clearly a point at which a critical proportion of the total delivered fleet has been parted out,” says Corne. “This creates an excess supply of airframe spare parts, and further additions drive the pricing to a stage where it is uneconomic to part out any more aircraft. This will vary by type depending on how long older variants remain in service, but it is generally hard to consider a strong economic demand for part-outs when retirements exceed 50% of the original fleet.”

“The decrease in demand for part- outs is directly related to the amount of aircraft remaining in service,” claims Spoors. “The 747-400 is a prime example. There are probably more 747-400 windscreens in the market place than there are active 747s!

“We are almost at the point in the life cycle of some aircraft, where their remaining valuable and in-demand assets will not cover the cost of the part-out and subsequent disposal of that aircraft,” adds Spoors.

In many cases aircraft being removed from service with little component value will still be disassembled rather than being parked indefinitely. In this situation the owner will attempt to claim as much value from the components as possible. “The owner will try to find ways to mitigate costs by selling even only a few items from the aircraft,” says Corne.

Examples of aircraft that might be parted out in the current market despite less demand for their components include: MD-80s, 737 Classics, older A320 family variants with CFM56-5A or V2500A engines, A340-200s and -300s and 747-400s.

“A340s can be good part-out candidates due to their limited operational attractiveness, but high levels of airframe systems commonality with the A330,” explains Corne.

“The outer landing gear and nose gear are interchangeable between the A340 and A330,” says Gregory. “There would still be a fair degree of wastage from an A340 teardown, however.”

Part-out values

The potential asset values that can be realized from parting out a commercial aircraft will vary considerably, depending on a variety of factors, including the aircraft type, age and condition.

There will be more demand for types with a large operating base where only a small fraction of the overall fleet has been parted out so far.

One such aircraft is the 737-800 of which there are currently 4,142 in service. Vandersluis confirms that, depending on the condition of components, a 737-800 with its two CFM56-7B engines is one of the highest- demand aircraft in the teardown market.

Oriel estimates that the current market value for a 15-year-old 737-800 in half-life maintenance condition with half-life engines is about $13.80 million. It estimates that the engine value will account for $9.00 million alone.

Engines are the most valuable assets in any part-out. “Engines are typically the driving economic factor for purchasing an aircraft for part-out,” says Corne. “Depending on condition they could account for 70-80% of the total asset value.

”After the engines, the highest value components will include the APU, landing gear and standard avionicsincluded in the line replaceable units (LRUs) fit list. “A 737-800 landing gear recertified to half-life status might have a significant value when sold either as removed, or recertified time continued,” speculates Vandersluis. “A GTCP 131-9B APU which has undergone a relatively recent shop visit, and which has more than 50% of LLP life remaining, will also command significant value due to APU commonality across the 737NG family. This provides good opportunities for lease revenues.” The avionics LRU fit on the 737NG family is consistent across early- and later-build aircraft, which helps to maintain aftermarket values.

ASI estimates that a typical 737-700 might have component asset values of up to $6.0 million. This would be realized by selling components in a mix of overhauled, serviceable and as-removed condition. To achieve the $6.0 million value, ASI believes that $0.5-1.0 million of shop visit investment would be required for certain components.

ASI speculates that flight-deck display units for a 737NG can have a value of $58,000-60,000 each and that quick engine change (QEC) kits are worth up to $250,000 each after allowing for about $50,000 of investment for a shop visit. Other high value items can include secondary heat exchangers, with a value of $145,000; and APU starter generators, with a value of $158,000. These values would apply to components fresh from overhaul or a shop visit.

ASI also speculates that the value of a 737NG landing gear could vary from $0.5 to $1.2 million depending on the life remaining.

The aftermarket value of components for a certain aircraft type can decrease as more airframes are parted-out. “If too many aircraft of a certain type are parted out the market will be flooded with spares and parts value will decrease,” explains Gregory. “The value of a 737NG thrust reverser started at about $1.20 million when the first aircraft were being parted-out, but has since fallen to $250,000-280,000.

”Aging aircraft with shrinking fleets that are being parted out because they have reached or are approaching the limit of their operational validity will have fewer in-demand components. Despite lower demand even older airframes are likely to have some components of value.

“The value of a typical 737-300 is probably about $1.2 million,” estimates Gregory. “There are probably only 300- 400 parts remaining that would be removed, with the rest being scrapped. These parts might be worth $100,000- 200,000.”

“The number of useful components will reduce for older aircraft, but they may have some commonality with younger generation types which could lead to a certain level of spares demand,” says Vandersluis. “Any rotating parts, such as constant speed drives (CSDs), integrated drive generators (IDGs) and starters are likely to see reasonable future demand, while a certain type is still flying. The value of these assets will, however,depend on the purchase price and recertification costs.”

Raw materials

“Once the engines and other useful components have been removed the remaining raw materials are recycled,” says Corne.

“There is a return on scrap metals, but there is a cost involved in conducting the scrapping process and for the disposal of hazardous materials,” explains Spoors. “Depending on the size of the aircraft the disposal cost can be more than the scrap value.”

“With current commodity prices, there is very little net value remaining in the raw materials,” says Corne. “The value is likely to be less than $5,000 for a narrow-body aircraft.?

Aircraft dismantlers

The majority of aircraft disassembly service providers are contracted to tear down aircraft owned by a third party. These organizations earn revenue from various services, including parking and storage, as well as those related to disassembly and disposal and third-party logistics.

Some dismantlers also have in-house parts trading services, and may buy their own aircraft to part out.

Many aircraft dismantling providers are members of the Aircraft Fleet Recycling Association (AFRA). AFRA was established in 2006 to provide a set of standards designed to promote the safe and sustainable management of end-of- life aircraft and components. AFRA claims its best management practice (BMP) guide has significantly improved the environmental and sustainable performance of end-of-life aircraft management practices. Although many dismantling organizations are AFRA members, they may not all be AFRA- accredited. AFRA-accredited dismantling organizations are those that have demonstrated that their processes are in accordance with AFRA standards.

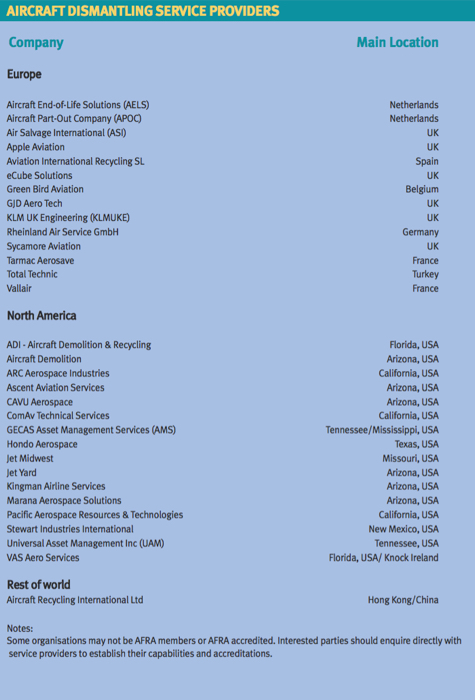

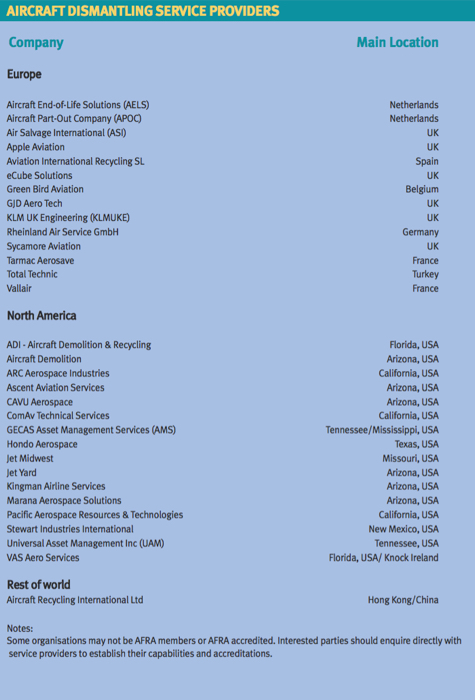

Some of the main aircraft dismantling service providers are identified here. This is not a comprehensive survey, and interested parties should make their own independent enquiries regarding specific capabilities and approvals.

Aircraft End-of-Life Solutions (AELS)

Aircraft End-of-Life Solutions (AELS) is an AFRA-accredited member, based at Woensdrecht Airport in the Netherlands. It offers disassembly services at its own facility or remotely on site at the location of an aircraft if required. “We have experience of disassembling aircraft from small 10-seat types up to 747s,” says van Heerden. “We can disassemble aircraft up 757 or A300 size at our own facility.”

AELS also offers storage services in association with a partner Part 145 provider. It also ensures that materials are recycled. It does not have in-house component repair capability, but can manage this process if required. AELS cannot remove parts in serviceable condition itself, but its Part 145 partner has this capability.

AELS does offer its disassembly, recycling and storage services to third parties including airlines, lessors and banks, but earns most of its revenue by buying its own aircraft to part out. AELS will remove engines during the part-out process but does not disassemble them. AELS also acts as a parts trader, selling components it has removed from aircraft.

Air Salvage International (ASI)

Air Salvage International (ASI) is based in the UK, and has been dismantling aircraft for 20 years. It does 50-60 part-outs per year for airlines and parts traders.

ASI is based at Cotswold Airport in Gloucestershire in the UK. It has been offering aircraft storage and dismantling services for 20 years. “We dismantle 50- 60 aircraft per year, which accounts for nearly 15% of annual global demand,” claims Gregory. “About one-third of the annual part-outs we perform are for airlines. The other two-thirds are for parts traders. We can dismantle all commercial types, either at our main base, or remotely if required.

”ASI does not disassemble enginesalthough it may remove QEC parts.

As a founding and accredited memberof AFRA, ASI takes responsibility for recycling or disposing of unwanted materials in an environmentally compliant fashion. Waste disposal takes place off site and is performed by approved waste management companies including AFRA-accredited metal recyclers.

ASI works closely with affiliate companies GCAM, an MRO and Skyline Aero, a parts trading company, also based at Cotswold airport. GCAM’s Part 145 approval means it can provide line maintenance and continuing airworthiness management for aircraft stored at ASI’s facility. Skyline Aero can offer on-site parts consignment services.

eCube Solutions

eCube Solutions is an AFRA- accredited member based at St Athan, near Cardiff in Wales. “We have experience of dismantling all commercial types at our main base,” says Corne. “We have multiple disassembly lines carrying out projects on A319, A330 and 767 types, and we are shortly due to start work on an A340-300 and 737NG.

“We also provide teams to perform remote part-outs worldwide, and recently completed disassembly projects on A330s and A340s in the Philippines,” adds Corne.

“Engines are removed as components in their own right during part-out,” explains Corne. “We do not disassemble them, but either ship them for return to service, or to a specialist engine part-out company.”

eCube Solutions offers storage services both at aircraft and component level. It also handles recycling requirements. “We take environmental responsibility for material recycling, although the physical activity is sub- contacted to specialist companies,” says Corne.

eCube Solutions provides Part 145 services by co-operating with strategic partner BCT Aviation. “This allows us to offer a range of maintenance tasks on virtually all commercial aircraft types,” explains Corne. “There are processes in place to remove components with ‘Serviceable As Removed’ tags, but in reality it is very rarely requested. Ourcustomers tell us that most end-users want fresh shop tags, which come with a higher degree of certainty in terms of reliability and the time to next shop visit, than a visually inspected used component taken directly from an aircraft.”

GECAS Asset Management Services (AMS)

GECAS AMS was acquired by GECAS in 2006 and is based in Memphis Tennessee. It has a dismantling facility located in Greenwood Mississippi, and is an AFRA-accredited member.

“We can disassemble all types of commercial and regional jets,” explains Haynes. This is work is mainly performed at GECAS AMS’ main facility, but it does also offer remote disassembly capabilities. GECAS AMS also manages off-site engine part-outs by a third party.

GECAS AMS ensures that all scrap metals from dismantled aircraft are recycled. This work is performed by an approved third-party scrap vendor for the recycling of scrap metals.

Components removed during the part-out process are placed in GECAS AMS’s inventory from where they are sold to a variety of customers.

GECAS AMS provides dismantling services for its parent company GECAS, but also provides part-out services to third parties. It also dismantles aircraft that it buys from third parties.

GJD Services/ GJD Aero Tech

GJD is based at Bruntingthorpe, Leicestershire in the UK. It includes GJD Aero Tech and GJD Services. GJD Services is an accredited AFRA member specializing in aircraft recycling and GJDAerotech is a certified part 145 maintenance facility which specializes in aircraft maintenance, storage and decommissioning.

GJD Aero Tech provides Part 145 services, including component removal and recertification, while GJD Services holds the relevant permits for recycling and disposal.

GJD can dismantle all commercial aircraft types either at its main base or remotely worldwide if required.

“We offer competitive parking rates at a number of locations, aircraft storage checks, care and maintenance, line maintenance, non-routine and ad hoc maintenance, scheduled maintenance up to and including A checks, and the inspection and recertification of removed parts,” explains Spoors.

“Post-storage and return-to-service maintenance, AD and SB compliance, component removal and recertification, AOG technical support and off-wing engine-support can also be provided,” continues Spoors. “We also offer certified engine storage, maintenance and disassembly services.”

KLM UK Engineering

KLM UK Engineering Limited (KLMUKE) is based at Norwich International Airport in the UK. “KLMUKE offers products and services to support the entire aircraft lifecycle for a variety of types including the E-170 and E-190 series, 737 classics and 737NGs, the A320 family, BAe146/Avro RJ and Fokker 70/100,” explains Alex Miller, customer support manager at KLMUKE. One of these services is parting-out.

AJ Walter is one specialist parts provider that provides component sales, loans and exchanges, and power-by-the-hour (PBH) rotable inventory support.

KLMUKE has five heavy maintenance bays across three hangars, along with a specialist aircraft part-out bay. It is an AFRA-accredited and UK Environment Agency-approved dismantler. “Many of projects so far have come about due to ‘deferred decisions’ with aircraft being parked on site by the owner while potential new operators are found,” explains Miller. “If no operator is found after a set period of time, the owner can choose to part the aircraft out at a reputable facility without the cost and inconvenience of a ferry flight.”

Vallair

Vallair is an AFRA-accredited member based in Chateauroux, France. It offers disassembly, storage and recycling capabilities. “As one of the founding members of AFRA we take our environmental responsibility very seriously,” says Anca Mihalache, sales and marketing manager at Vallair. “At the end of the dismantling process we use a recycling company that cuts the fuselage to recover and reuse the metal.”

“We can dismantle narrow-bodies, including A320 family, 737 Classic and 737NG airframes,” continues Mihalache. “Our dismantling area can process 12 aircraft per year.

”Vallair provides dismantling services for third-party aircraft, but also sources its own airframes for part-out. It has built up an inventory of A320 and 737 components. “We have also dismantled more than 10 CFM56-5A engines,” adds Mihalache. Vallair does not dismantle engines at its facility.

This inventory of airframe and engine components is available for sale or lease. “We sell elevators, inlet cowls, fan cowls, thrust reversers, radomes and other parts in serviceable condition with a fresh tag,” explains Mihalache. “We also have an in- house repair shop for engine nacelles and flight controls.

”VAS Aero Services LLC (VAS)VAS is an aftermarket parts specialist with experience of managing the aircraft disassembly process for third-party airframes and engines owned by airlines, MROs, OEMs and leasing partners. VAS also acquires assets for teardown to distribute material into its preferred supplier agreements with strategic customers. In the past, it has used preferred third-party MROs andteardown providers to perform disassembly work scopes.

VAS is now included as a disassembly provider since its owner America Aero Group recently acquired EirTrade Aviation (Ireland) to complement VAS’s existing aftermarket services. “VAS can now offer aircraft disassembly services through EirTrade Aviation’s facility located at Knock Airport, Ireland,” explains Kevin Ferreiro, business development manager at VAS. Additional services available to customers are aircraft, engine, and inventory storage and recycling programs.

“VAS has experience of managing aircraft teardowns for most commercial aircraft models,” adds Ferreiro. Upcoming disassembly targets include A320 and 737 family aircraft and other models.

“Most of VAS’s business includes marketing and reselling components from parted-out aircraft and engines directly to major airline, MRO and OEM customers,” explains Ferreiro. “VAS sells direct to over 1,200 of the largest end- users in the aviation market. Other VAS capabilities include: surplus inventory consignment for re-distribution in the aftermarket; engine and inventory exchanges; inventory supply programs and sourcing portals; engine maintenance management; aircraft and engine technical support and inventory analysis; and marketability.”

Other

A number of other organizations advertise aircraft dismantling services. In Europe these include Apple Aviation and Sycamore Aviation in the UK, AircraftPart-Out Company (APOC) in the Netherlands, Aviation International Recycling in Spain, Green Bird Aviation in Belgium, Rheinland Air Service GmbH in Germany, Tarmac Aerosave in France and Total Technic in Turkey (see inserted chart).

Some of the largest storage and teardown facilities are in the United States (US). There is a particular concentration of providers in Arizona where low humidity levels mean aircraft can be stored for longer periods without experiencing corrosion issues. Examples of Arizona-based dismantling providers include Aircraft Demolition, Ascent Aviation Services, CAVU Aerospace, Jet Yard, Kingman Airline Services and Marana Aerospace Solutions. Other US- based dismantlers include: ADI – Aircraft Demolition & Recycling in Florida; ARC Aerospace Industries; ComAv Technical Services and Pacific Aerospace Resources & Technologies in California; Hondo Aerospace in Texas; Jet Midwest in Missouri; Stewart Industries International in New Mexico; and Universal Asset Management Inc (UAM) in Tennessee.

Dismantling providers are also located elsewhere in the world. One notable example is Aircraft Recycling International (ARI) Ltd, which was established in 2014 and is headquartered in Hong Kong. ARI plans to operate the largest dismantling facility in Asia. The first phase of this facility, which will be located at Harbin Taiping International Airport in China, is due to be operational by 2017.

Article source